Beneath the Shadow of the Bauhaus: Another Story Encountered in Australia

One of my greatest passions is wandering through the dense jungles of art galleries, a habit I indulge in regularly. Recently, I travelled to Canberra to visit the latest exhibition: Cézanne to Giacometti, where a collection of both European and Australian artworks were being displayed.

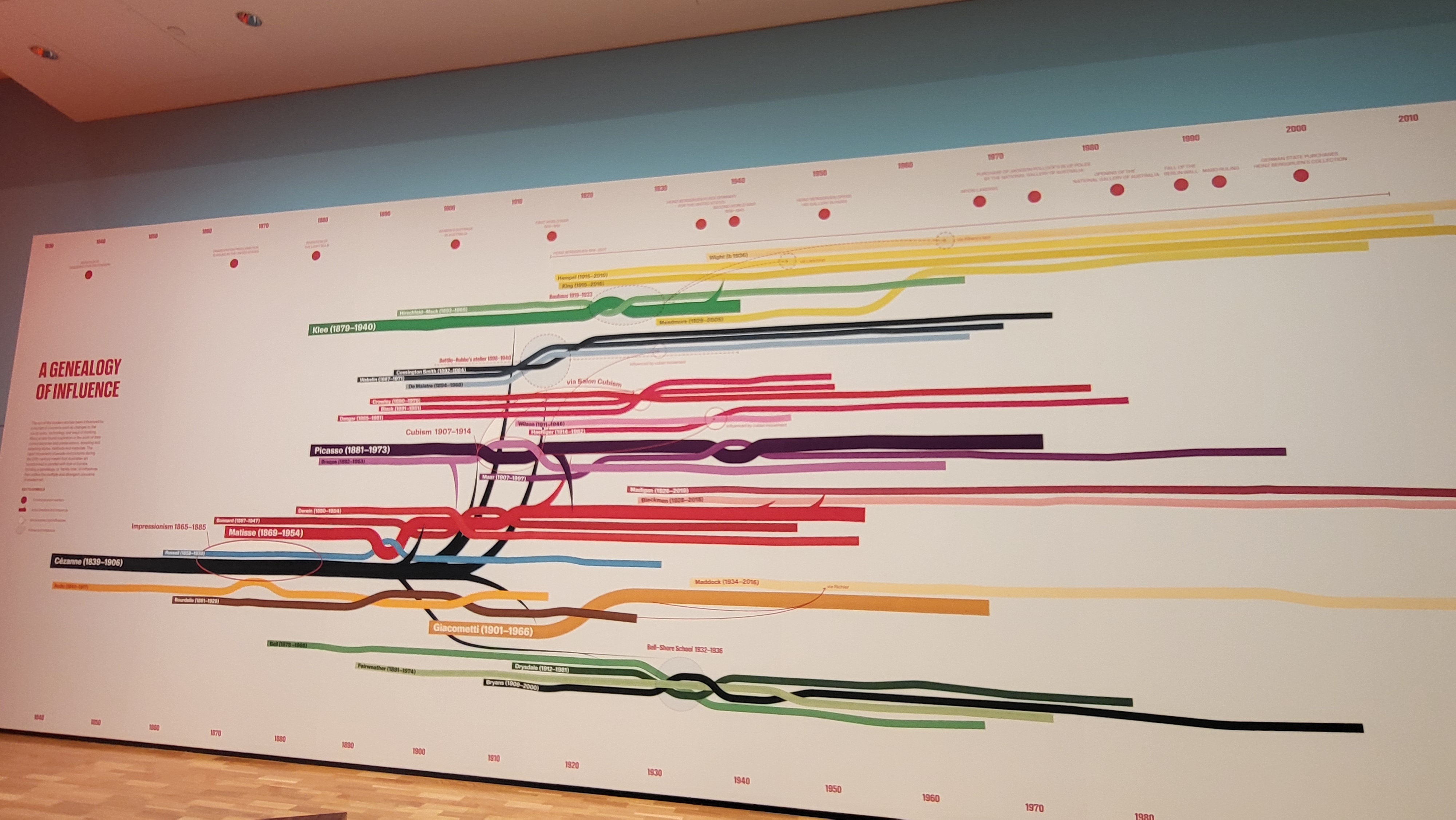

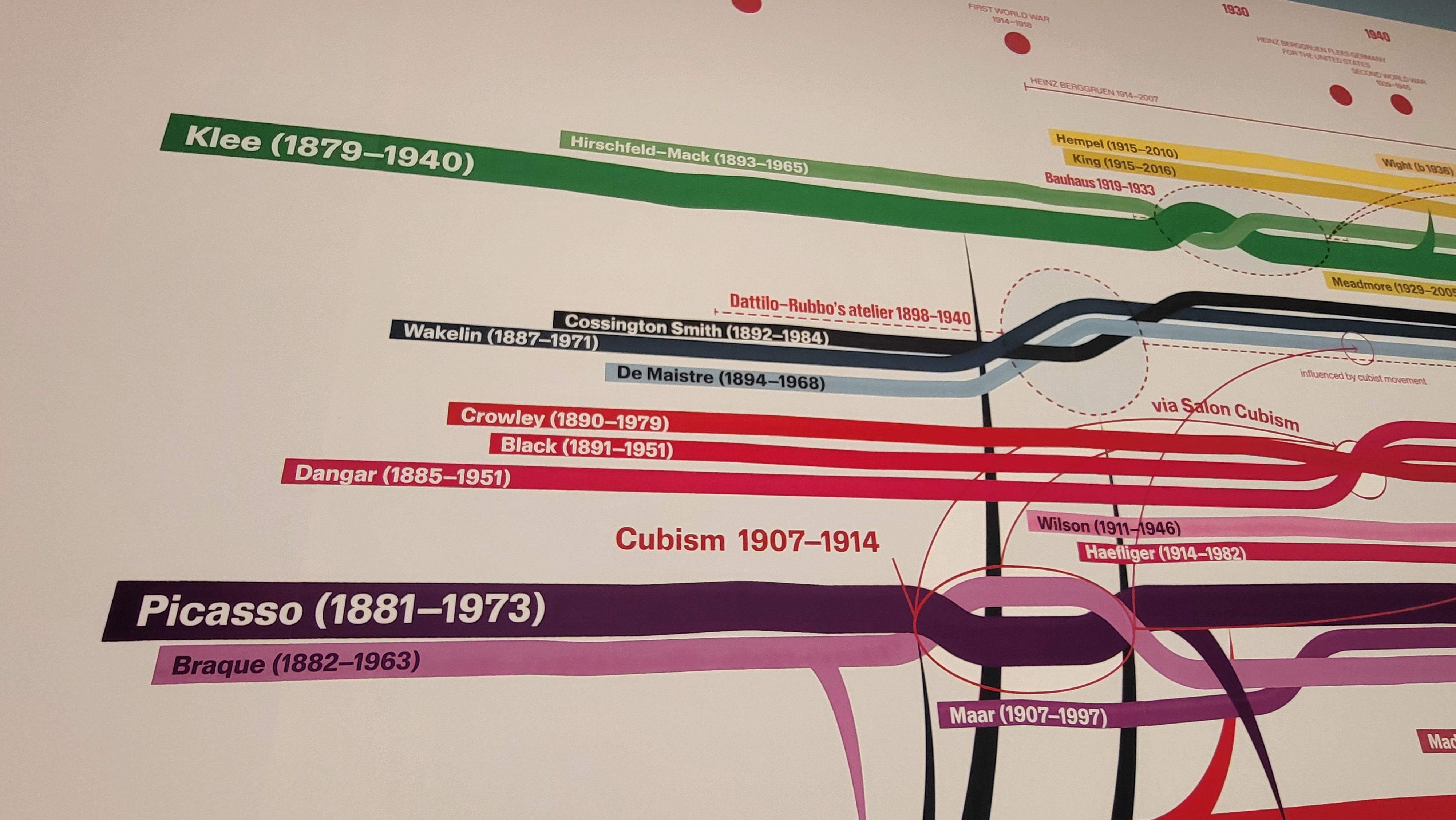

As I entered the gallery space, my gaze was drawn to a sprawling mural: a visual tapestry linking each artist to another across eras, styles, and movements. Though their brushstrokes and philosophies varied, the artists were strung together like echoes of a singular vision, their lineages folding inward and outward, circling back. At the heart of this web lay the formation of the Bauhaus - a revolutionary force that wove modern design, fine art, and craftsmanship into one. Many of the threads in this mural, whether through influence or ideology, seemed to trace back to the Bauhaus, its spirit of innovation rippling through time.

In a small dark room in the exhibition, I read the words lettered on the wall: Bauhaus in Australia. A painting on the wall caught my eye as I went to scrutinize it. The exhibition had been set up so that Australian paintings which were inspired by Bauhaus artworks would be displayed together.

Desolation, Internment Camp, Orange, NSW by Ludwig Hirschfield-Mack seemed simple enough to decipher from a distance. A man stood beside a wire fence so commonly associated with concentration camps, gazing up into the stars. At first glance, I imagined a Holocaust survivor, hollowed out by grief, framed by the sharp geometry of prisoners. The artist, a Bauhaus member, was deported from Germany to Australia, where Ludwig Hirschfield-Mack spent much time exploring the internship camps in Hay and Orange as an enemy alien.

However, the painting made me think again, as I squinted closely at the title. As an Australian, the painting made me think of one of many Aboriginals suspected and suppressed for their identity, stretching into the Stolen Generations. The Europeans took Aboriginal children from their families over a 60-year period (1910-1970). These children are now known as the Stolen Generation.

During this time, thousands of Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families by government authorities and church missions. The aim was to assimilate them into white society by erasing their language, culture, and identity. Many of these children were placed in internment camps, tortured, and forced to adopt new identities, growing up completely disconnected from their heritage.

This practice left deep scars not only on the individuals taken but also on entire communities. Families were torn apart, connections to Country were severed, and generations grew up disconnected from their heritage. Most of the Stolen Generation never met their families in their lives.

Although the Australian government has expressed their apologies verbally over the decades, no serious action was taken to extract the Stolen Generations out of their current, poverty-polished life or restore the Aboriginals' former wealth.

The painting made me think about the Europeans, celebrated because of their efforts in defeating the Nazis. Yet, the painting to me realizes how easily we identify others' injustices, and how often we overlook the ones closest to home.

Although I am doubtful Ludwig Hirschfield-Mack's brush spoke this deep, perhaps he intended us to find information in his silence.

Up until going into the exhibition, I was unaware of any Bauhaus members who lived in Australia. I was exhilarated!

Member discussion