Bottom’s Dream : Shakespeare for Children

A cool breeze from the Sydney Harbour pier slipped through the open glass doors. The excitement of younger children echoed through the play theatre. At the entrance, a banner announced a children’s adaptation of one of Shakespeare’s most celebrated plays. Bottom’s Dream retold the story and ‘dream’ of Nick Bottom, the unforgettable secondary character from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. As I watched, I found myself drawn to its themes of transformation and illusions. Beneath the folly of its asinine characters, however, hidden motifs seemed to stir.

Shakespeare survives most vividly when he is reimagined. Nowhere was that clearer than in Bottom’s Dream, a blend of both fantastical creatures and mortals in a forest. The adaptation stripped the bawdiness of Shakespeare away, the product remaining full of vanity and confusion. It offered enough silliness for children to laugh at, and enough recognition for adults to smile knowingly.

The play focuses on Nick Bottom, a boastful but endearing weaver aspiring to become an actor. Along with a group of fellow craftsmen, Bottom prepares to perform a play called Pyramus and Thisbe, a story uncannily similar to Romeo & Juliet. Bottom auditions for every role, convinced he can outshine his companions.

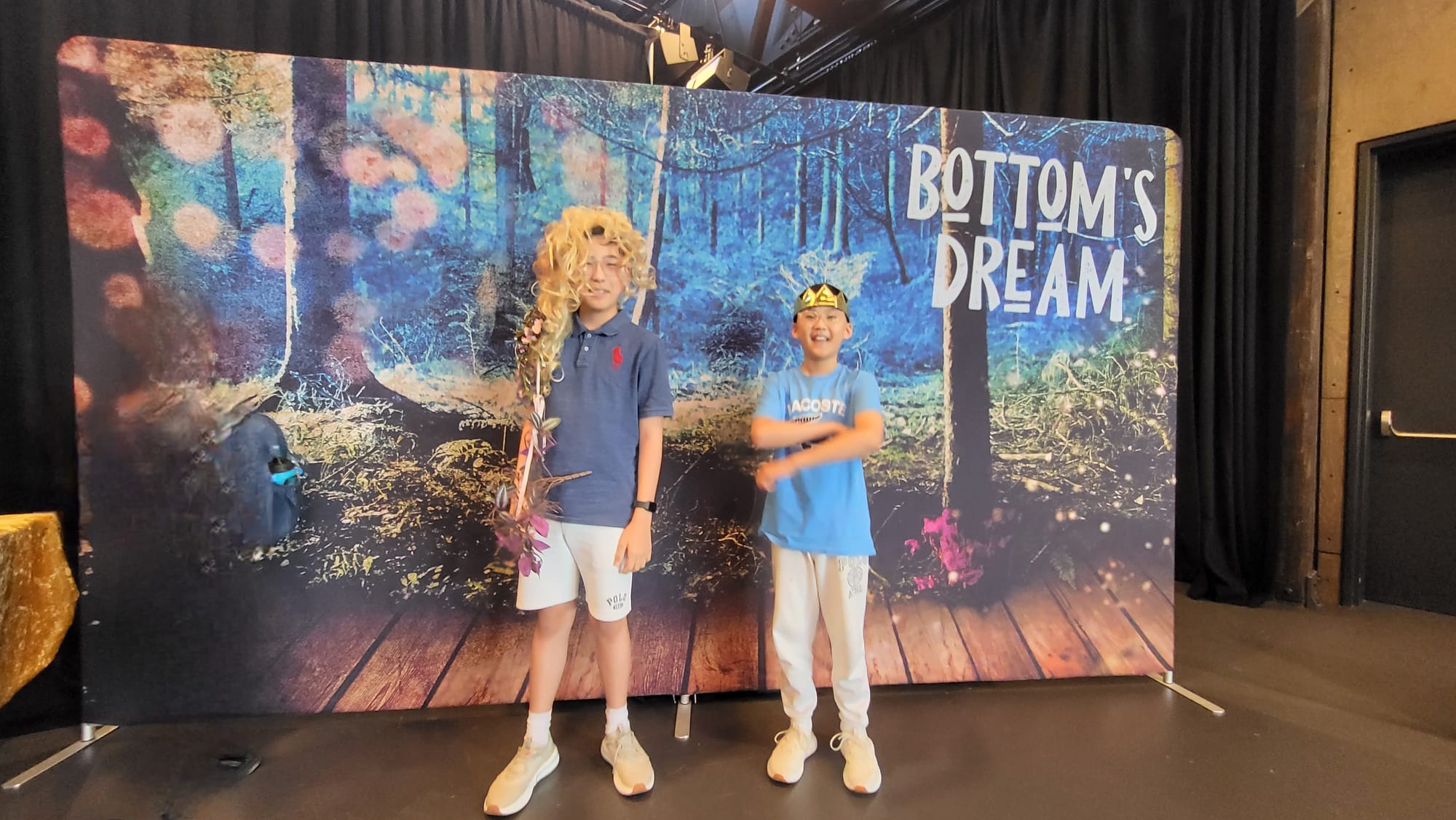

Children sat on the edge of their seats. Oberon the fairy king sent his servant, Puck, to play a trick on the estranged queen of fairies. A small child next to me giggled, her dimples expanding, as the servant cast a spell, transforming Bottom’s head into that of a donkey. The fairy queen, Titania, is bewitched to fall in love with him. For a time, Bottom enjoyed this bizarre attention, unaware of his transformation, until the spell was lifted. He returns to his ordinary self, albeit more learned. What remains with him is the ‘memory’ of a strange and wondrous dream he cannot fully explain.

As the play unfolded, I noticed how Bottom directed his speech towards the audience. His catchphrase, “I had a most rare vision,” bounced around in my head, as I thought of the intensified focus on the blurred lines between reality and fiction. After being bewitched to take the resemblance of a donkey and meeting fairies, creatures ‘mythical’ to humans, Bottom scratches his head and wonders about the reality of such situations.

When the spell that bound Bottom into a donkey broke, he waved the events off as a dream. In the play, the theatre acted as a device in which to shake our sense of reality. Underneath lies a truth: we too struggle to make sense of experiences that shake our understanding of the world. Sometimes, I would wake up, unsure of the reality of my dream. This reflects a classic Shakespearean motif. He often pressures the audience to question everything.

Shakespeare goes a step forward, crowning Bottom’s head with an invisible jester hat. Bottom, put bluntly, is the fool of the show. He is boastful and unorthodox, especially when he attempts to play every character in Pyramus and Thisbe. Yet, the very foolishness Bottom is gifted with reveals truths of the world. The disastrous ending of Pyramus and Thisbe highlights the inevitability of foolish flaws. Yet, through embracing them, people are united. When Titania falls madly in love with a donkey-headed Bottom, Shakespeare exposes the blindness of love - irrational, yet profoundly human. At its most foolish, Bottom’s Dream reveals such irrationality.

As the actors bowed and the studio lights warmed the stage, the spell dissolved, yet its vision lingered. Bottom’s Dream became more than a comedic Shakespeare adaptation for children. Through the characteristics of Bottom’s ‘fool’, Shakespeare asks the audience to question everything. The play also suggests further truths, such as the unpredictability of love and human flaws. In itself, Bottom’s Dream was a most rare vision. In the so-often overlooked perspective of absurdity lies a mirror reflecting our very selves.

Member discussion