Five Nights at Freddy's

Some time ago, I was introduced to a survival horror game quite unlike many others. Five Nights at Freddy’s turned a bright children’s restaurant by day into a place of isolated danger at night. In a sense, the game was an artwork, blurring nostalgia into hidden tragedies and social context.

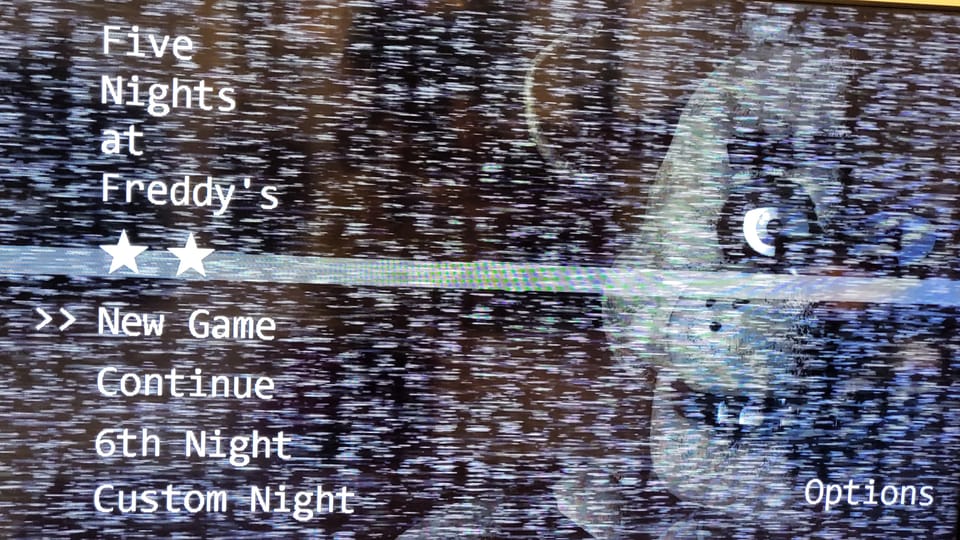

As I turned on the screen to the sight of a brown bear in his dapper top hat, I clicked play, the black screen shifting into a security office, darkness hanging overhead.

I was playing as Michael Schmidt, the newest night watchman at Freddy Fazbear’s Pizza, a “magical place for kids and adults alike.” As I jammed my fingers on my controller, a news clipping in the game caught my eye: ‘5 children disappear at local pizzeria’.

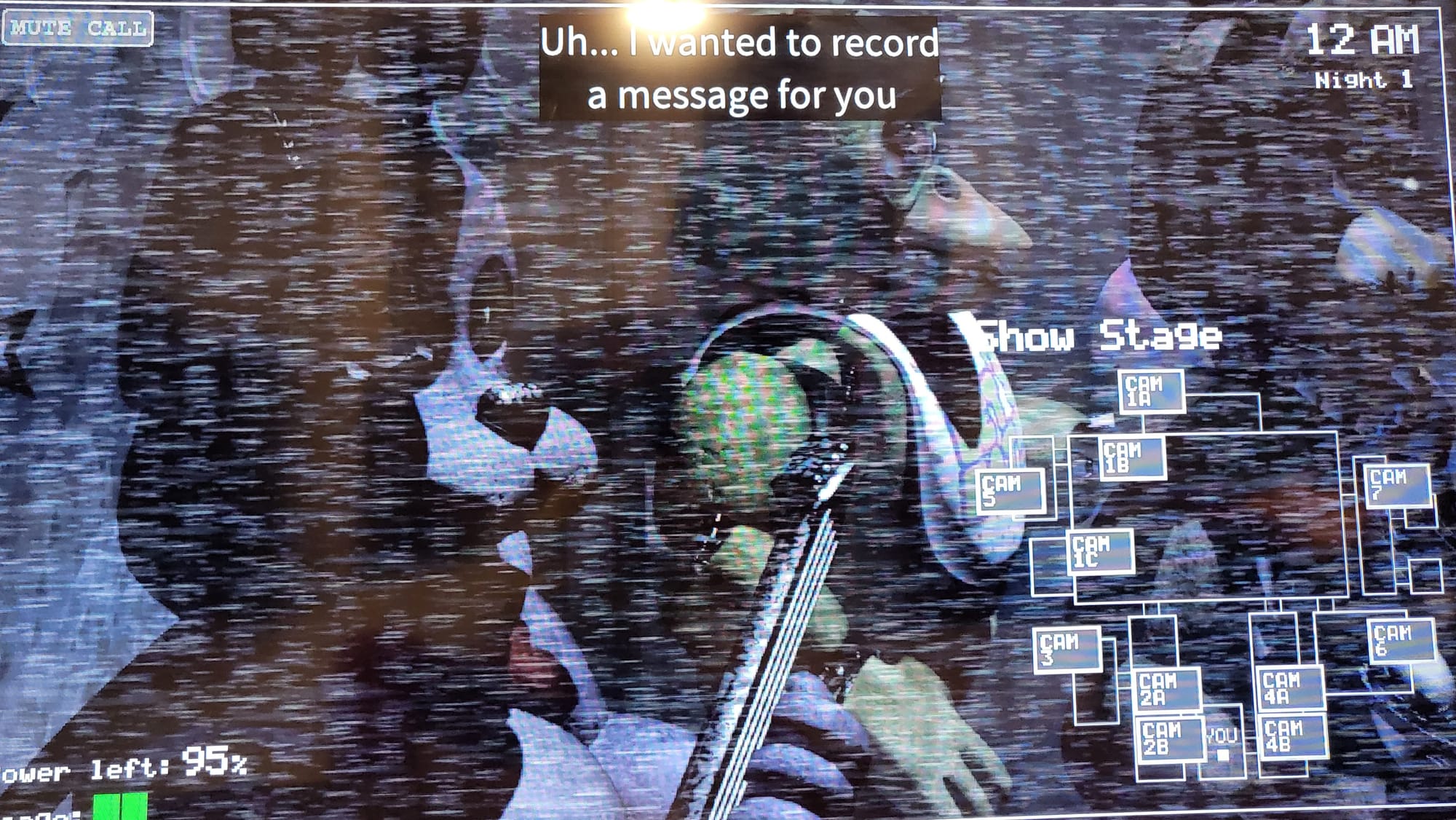

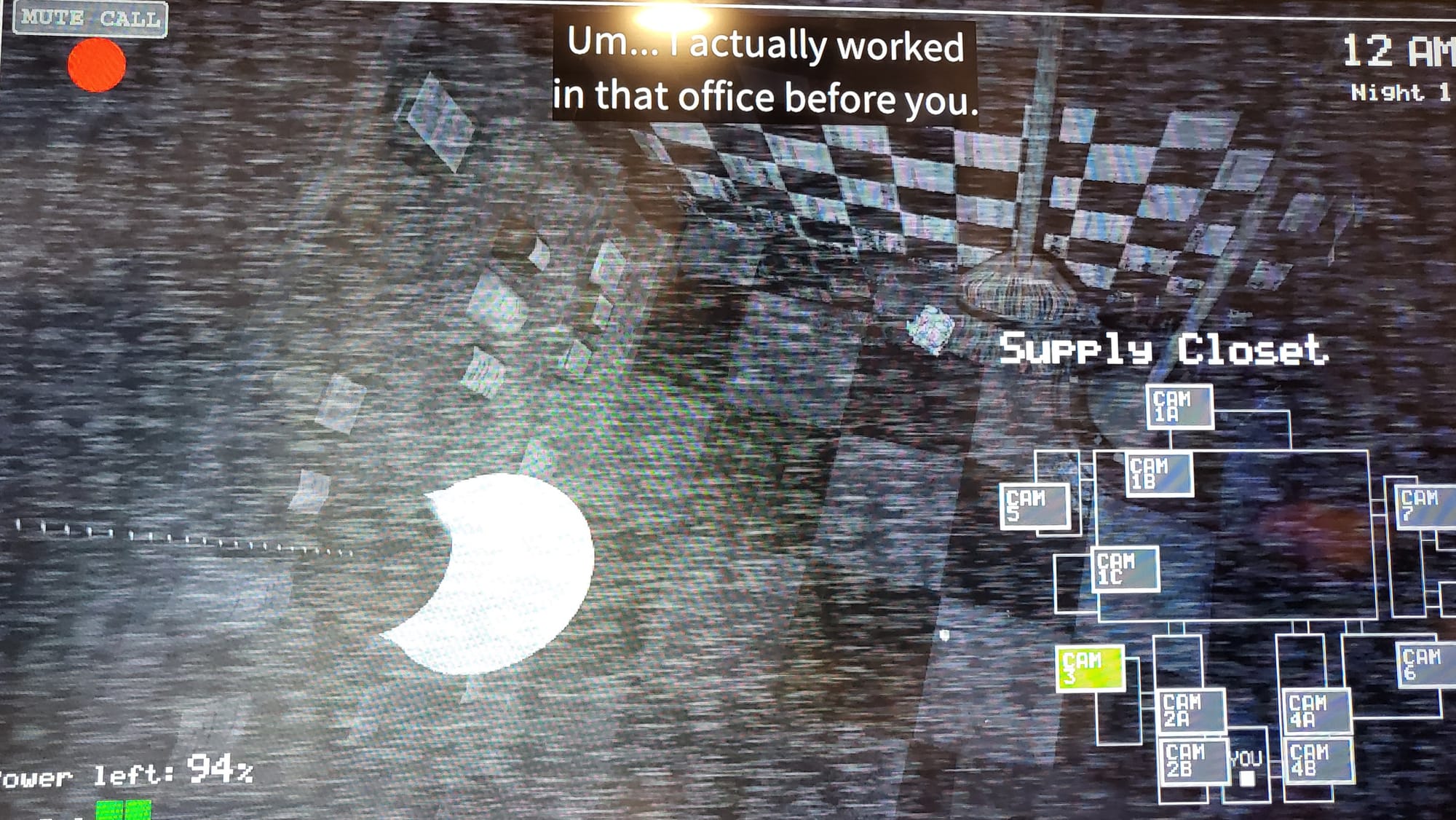

I gulped as the phone started ringing on the security desk, flashing red among the clutter of fans, monitors, soda cups, and rolled-up paper.

I listened as a voice laid out the basics of my new role.

“At night the animatronics (animal mascots) wander around, and if they see you, they’ll stuff you into a Freddy suit, so close the doors in the office to lock them out.” Thus, in this game, I had to close the doors to survive.

On the cameras, the stage revealed the animatronics: Bonnie the rabbit with a guitar, Chica the chicken with her “LET’S EAT!!!” bib, Freddy the bear in his top hat, and Foxy the Pirate lurked behind red curtains. The cameras glitched, emitting static, as I turned the monitor on and off. Glancing back at the cameras, I gulped when I saw the show stage missing Bonnie. In the distance, I picked up the clicking of servos approaching.

There was more to Five Nights at Freddy’s than simply killer animatronics. The game’s backstory reveals a co-founder of Freddy Fazbear’s Pizza named William Afton - better known as ‘Purple Guy’. Purple was a colour of nobility and power for centuries, while displaying corruption in other, more cultural senses. This matched perfectly with Afton’s personality, who often compared himself to a being with immeasurable power, yet cruel.

Afton was a serial killer, responsible for the disappearance and murders of the children in the newspaper clipping. In the game’s lore, the missing children were not simply forgotten, their souls inhabiting the animatronics and vengefully killing the night guards. However, even revenge offered no release, bound in endless cycles of violence and fear.

Often overlooked in discussions of Five Nights at Freddy’s is the detail of the night guard’s paycheck. For surviving five consecutive nights under the threat of death, I received only $120 - below even the minimum wage standards of 1993, around which the game is set in. However, Schmidt still returns, night after night. In his own work, he remains loyal to Fazbear Entertainment, the company behind Freddy Fazbear’s Pizza, without thinking of the very reasons or consequences of his actions.

This is further underscored by the fate of Phone Guy, a disembodied voice who guides the player each night via recorded messages. However, as in Night 4, Phone Guy, the one figure who seems to understand the system, cannot survive it either. Even his record as ‘Employee of the Month’ for twenty-two consecutive times proves meaningless. Knowledge, loyalty, and experience hold no weight.

Both Michael Schmidt and Phone Guy reminded me of events in George Orwell’s Animal Farm, where the animals, while obeying, are seen as disposable. Such an example is Boxer who, despite his status as the hardest worker in Animal Farm, meets his own demise at the hands of the farm of which he devoted his life to. Every employee is disposable, and survival itself is only temporary.

Five Nights at Freddy’s is more than a game. It symbolises commentaries on exploitation and vicious cycles, all as a web of allegories. As I once again pick up my controller and Schmidt sits once more at the desk, watching the shadows shift across the stage, I realise the true horror isn’t the jump scare - it’s the resignation. Come tomorrow, I’ll be back again. What happens at Freddy’s stays at Freddy’s.

Member discussion