Review: Morris Gleitzman's Once

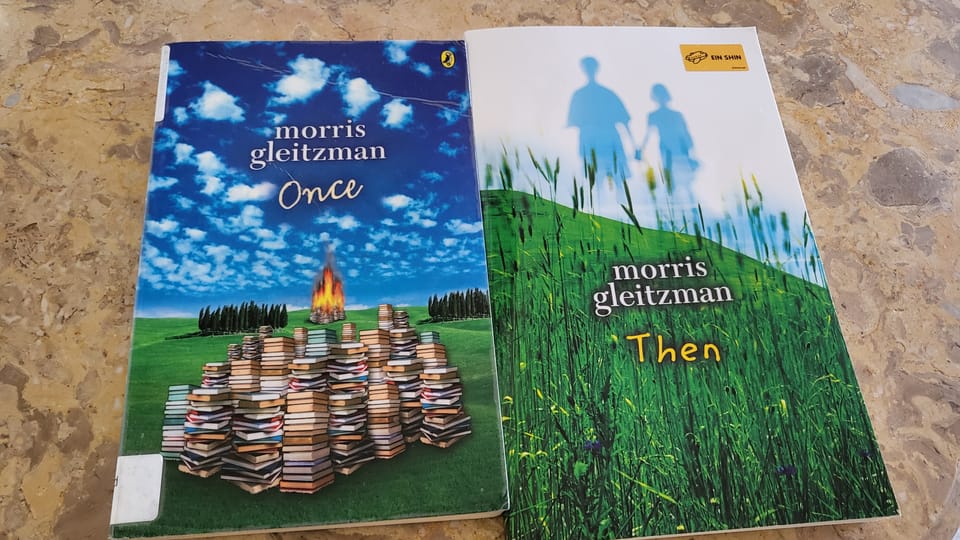

Recently, I read Once when I met Morris Gleitzman, a bestselling Australian author who has been writing for over 40 years. With one look at the rectangular block-like books and terrain reminiscent of a Minecraft biome on the cover, the eyes of my friend, Bodhi, twinkled. “We get to read a Minecraft book? Cool!”

I shook Bodhi’s hands off the cover of my book, as I began to read the first page.

In an orphanage in Nazi-occupied Poland, a small boy, Felix Salinger, sits on a long wooden bench, shifting his buttocks as the splinters of the wood push against his pants. Wiping his fogged glasses with his fingers, the boy shoves it back onto his nose, as he looks into his steaming bowl of soup. His eyes widen as he catches a flash of orange. It couldn’t be!

His favourite food: a carrot. Felix’s eyes darted around. This is a sign from Mum and Dad! It’s here to show me that they’re coming back for me! As he glanced once more to his side, he stuffed it down his pocket; this event would change Felix’s fate and his perspective of the world altogether.

I enjoyed the book greatly, due to its accuracy to the average child’s conscientiousness approach in the Holocaust. Yet, my mind recalled my knowledge of WWII. In The Pianist, where a Jewish survivor is helped by a Nazi officer similar to how Felix befriends a Hitler Youth, both out of their moral compass. As I read Once, I was also reminded of Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Both Frankl and Felix, the protagonist of Once, find strength in spinning their spiritual freedom.

As the story progresses, Felix relies on his own stories to help him understand the world around him. Having been raised in an orphanage with little proper education, including the war around him, Felix relies mostly on his own imagination to make sense of his surroundings, culminating in his own stories. When Felix witnesses ‘men in armbands’ burning Jewish books, he jumps to the conclusion that ‘Jewish booksellers’ somehow angered the men. As in the case of Felix, storytelling helps him endure pain and gives him courage, supporting his own sense of hope.

Felix’s hope is initially naïve - he interprets a carrot in his soup as a sign from his parents and believes his journey will end in reunion. Yet, when he meets a Jewish dentist, Barney, caring for orphaned Jewish children, and Zelda, a girl orphaned after her parents were killed by the Polish Resistance, his view shifts. He comforts her not because it advances his own dream, but because he could not bear to leave another’s pain uncomforted. Later, among Barney’s hidden children, Felix shows the same instinct to care, seeking to reassure those paralysed with fear. What begins as a quest to find his own parents becomes one of protecting others.

When Barney and the children are eventually caught, they are put on a train heading to a death camp. While Felix and Zelda urge the others to jump out, Felix tells of a story where outside the train there was freedom, that the fields beyond held stories waiting to be lived, not ended. His stories were not just escape, but a gift of courage, urging the children to leap into an escape. In that moment, storytelling became more than imagination - it was empathy turned into action, and hope almost powerful enough to push frightened hearts toward survival.

As I close the covers of Once, a question echoes in my mind: is hope merely a fragile illusion we cling to, a story we tell ourselves against despair? For Felix, hope begins as a belief that a carrot is a sign from his parents. Yet it grows into the courage to comfort Zelda, to reassure other children, and to use stories on the cattle train to inspire escape. Ultimately, Felix transforms the instinct to survive into an act of shared humanity.

I smiled at the thought that Gleitzman himself might not be so different from Felix. He also slips us a ‘carrot’ in his stories; even with everyday objects one can find hope.

Member discussion