A History Nut's Reflection

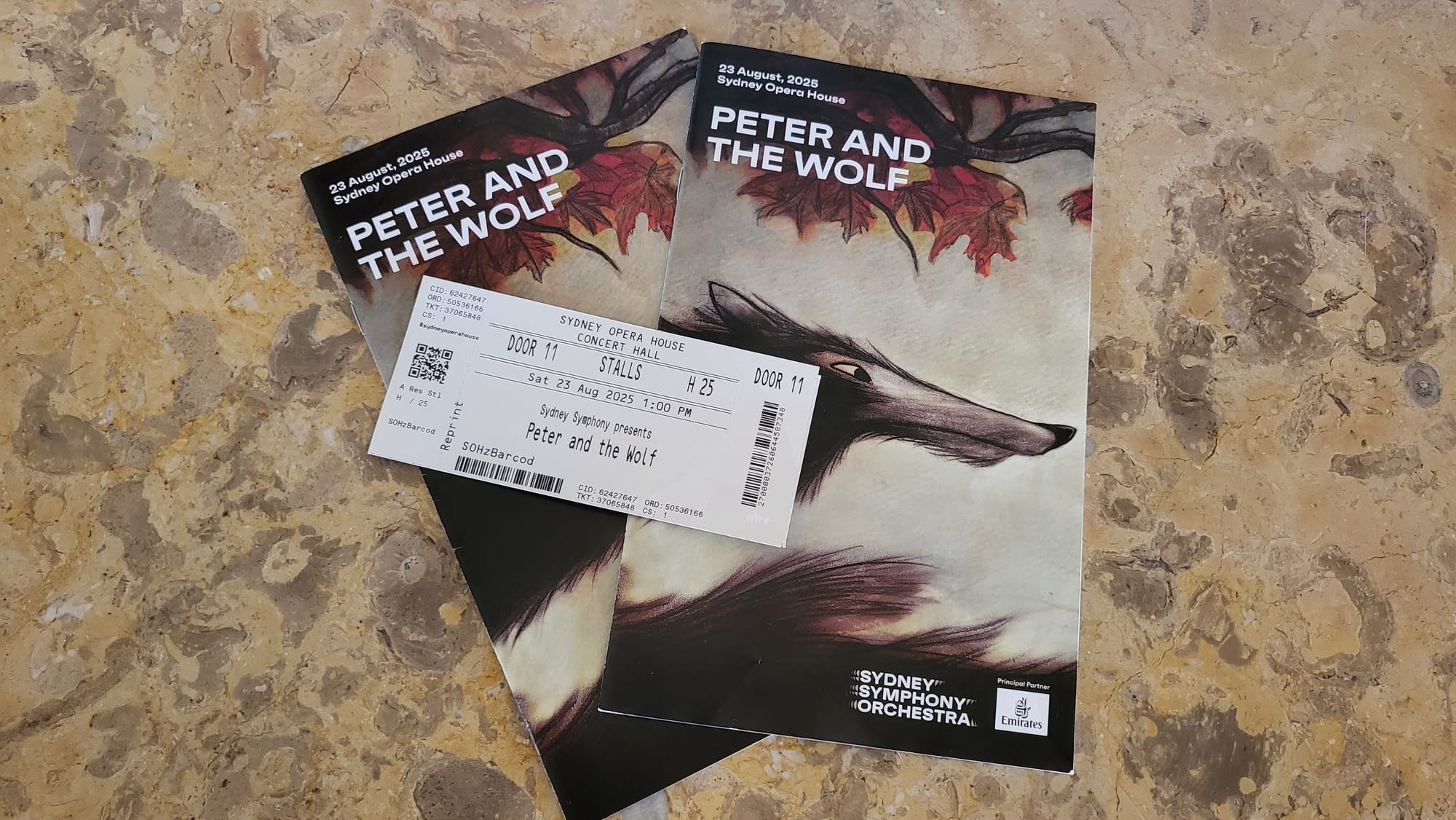

Seated in H25, at the centre of the conductor’s podium, I listened to the orchestra tune their instruments. Looking around the Concert Hall of the Sydney Opera House, glowing with both design and sound, I picked up the ambience of family conversation reverberating through the acoustic reflectors. My ears twitched as the first notes played: Peter and the Wolf had begun.

This symphonic fairy tale was unlike many others, created to introduce young people to the orchestra and familiarise themselves with the instruments. The composer, Sergei Prokofiev, a Russian, aimed to create a piece that would bring children into the world of classical music, and was so inspired by the idea that he completed it in only four days. The concept was as much social as it was musical: even without pictures, one was able to look through the story with audio.

The string instruments personified a carefree Peter, as he went out of his house to play with his animal friends. His grandfather’s voice growled a bassoon, as he scolds his grandson for playing near the ‘dangerous’ forest. The boy’s animal friends emerged through the woodwinds, their lines sarcastic yet edged with boldness. The duck enjoys a swim in the pond, the bird argues with the duck on a tree, and the cat sits, polishing its teeth, eyes set on the duck.

The wolf, charging out of the forest, is set through the French horns, consuming the duck in one gulp. While the other animals escape, Peter makes a noose with a rope and climbs onto the tree, capturing the wolf by its tail while the timpani and bass drums announce the arrival of the hunters and their rifle shots.

Unlike many other formal performances, Peter and the Wolf was punctuated with mistake-free and smooth narrations of the unfolding events. The accompaniment of the music brought the narration further to life. Likewise, what I especially enjoyed were the unique interactions between the performers of the piece. Back and forth, the conductor, Benjamin Northey, and the narrator, Tim Hansen, interacted in a play-like fashion - our giggles carrying through the acoustic reflectors. At times, the instruments spoke of brightness rather than defiance, and defiance rather than brightness. Prokofiev uses this contrast between the instruments to establish a clear line to the audience younger than most.

Beneath the surface lay a second story, one shaped by the world in which Prokofiev composed. Different characters symbolised different themes. When Peter and the Wolf was created, Soviet society held deep expectations for such ‘Pioneer’ traits, considered important by a Soviet children’s communist organisation, such as vigilance, bravery, and resourcefulness. These ‘traits’ are all shown by Peter, who, despite any attempts from his grandfather to warn him of the dangers of the wolf, ultimately captures the wolf.

In Peter and the Wolf, I found the case of the swallowed duck most interesting. When the wolf swallowed the duck, I heard gasps from the children around me, my heart building to a crescendo. While most fairy tales end with neat and ‘happily-ever-after’ resolutions, Prokofiev ignores this basic structure and allows the duck to be swallowed whole, neglected even by Peter’s own courage and act of bravery. This may reflect on Prokofiev’s Soviet society in the 1930s, particularly when even victories carried hidden costs. When Prokofiev composed the piece, the alliance with Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union was seen as a recent victory, though ultimately Hitler betrayed Stalin. The case of the duck highlights an oppressive, unfair, and dangerous world. Even when Peter and the hunters put on a victory parade of the wolf, the duck can be heard quacking in the belly of the captured wolf, depicting the hollowness of Peter's quick thinking and bravery: the so-called traits of ‘Pioneering’.

As the concert doors opened and we poured out, I thought about the nature of this particular piece. While Peter and the Wolf takes the case of a children’s fairy tale played by music, Prokofiev reveals a layer of hidden Soviet societal issues and motifs. The duck’s absence from Peter’s ‘family’ reminded me of a dangerous world while Peter’s own personality is drawn from the Soviet ‘Pioneer’ program.

I particularly resonated with Prokofiev’s dream of spreading the love of music to children. Peter and the Wolf suggests that its true success lies not only in teaching children to recognise instruments.

Music is a language, flattering, deceiving, and revealing as it chooses.

Member discussion