Questioning Our Reality: Down the Rabbit Hole of Rene Magritte

The Art Gallery of NSW is a children’s paradise, yet few realise it. Visiting isn’t about art: it’s an opportunity for me to practise the art of drinking Coke, a sacred tour de force my friends never share. On these visits, Coca-Cola isn’t always the highlight, as I am sometimes allured by exhibitions. The arrival of Rene Magritte’s exhibition in Sydney, however, put me into a trance, the same Paul McCartney was trapped in. It prompted me to return thrice, also instructing me to rediscover Rene Magritte’s surreal genius.

Before his quintessential bowler hats and surrealist fame (the art of releasing the creative potential of unconscious minds), Rene Magritte lived an early life shrouded in mystery, much like his paintings. When he was 13, his mother, a bowler hat-loving milliner, committed suicide due to depression; he started playing in the cemetery, perhaps to be ‘linked’ with his mother with an unrealistic union. Once on a visit, he witnessed an artist ‘from the capital’ painting the graveyard: the moment that pivoted his future life influencing him to move to Paris. It was here that Rene Magritte painted his share of his lifetime, one of the most iconic being The Lovers.

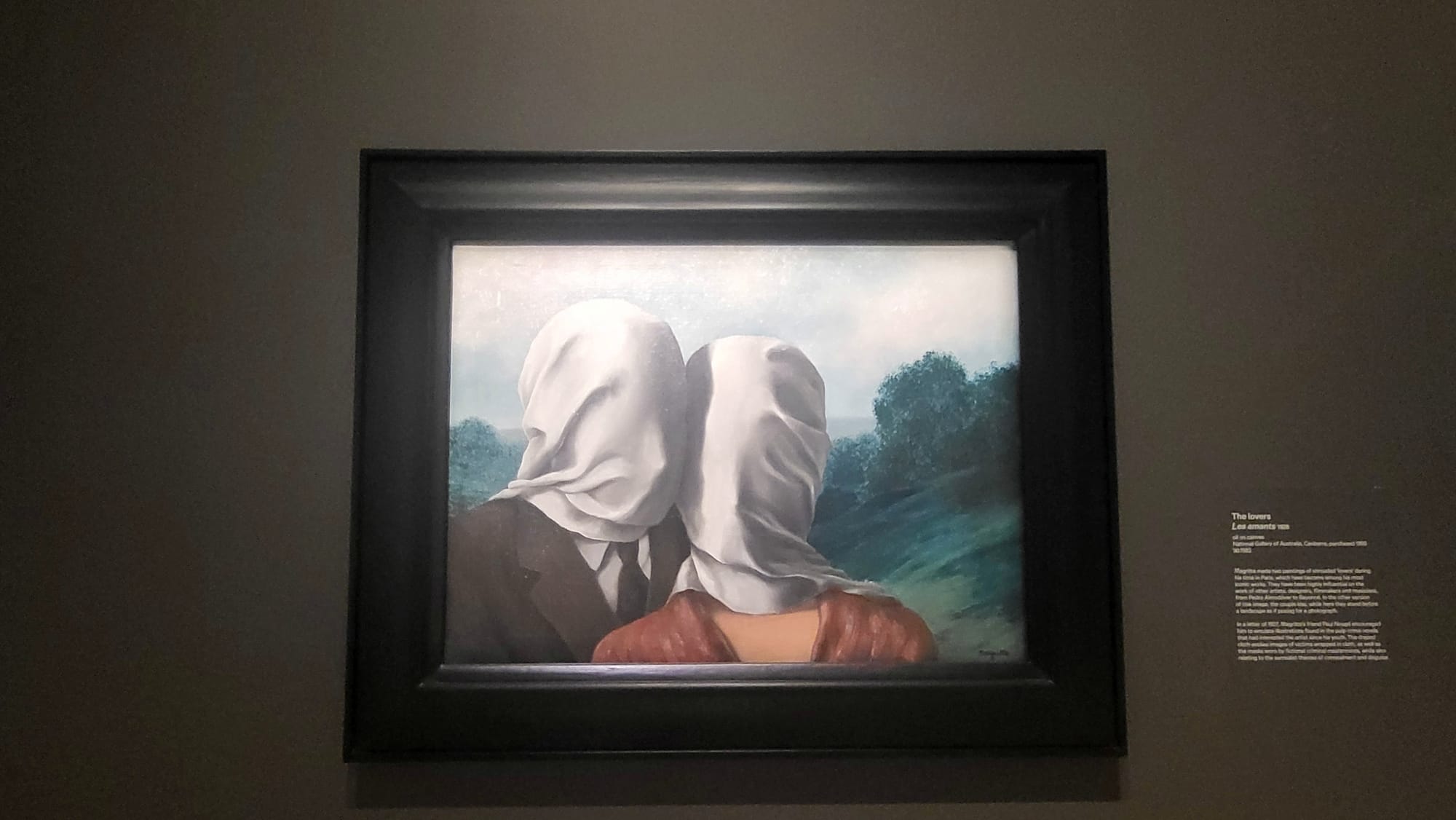

Throughout Magritte’s illustrious career, he explored different sub themes of surrealism. In The Lovers, a classic couple from an Instagram post is depicted. However, there is a fabric cloth curling onto their clothes, keeping them physically apart: blind Romeo and Juliets. The lovers are unable to communicate with each other, impractical and frustrating. The meaning behind this masquerade is unclear, albeit there are many plausible theories.

One of the most prominent explanations is from Magritte’s gritty love for crime novels. Behind the curtains, Magritte may have drawn inspiration from Fantômas, a masked fictional criminal he liked. Another theory is that the fabric may have evoked Magritte’s mother’s suicide when he was only 13. Due to long bouts of depression, she escaped from her locked bedroom, only to be found and dragged out of River Sambre later, her nightgown concealing her face. The Lovers is indeed a journey through time, yet the Human Condition beats above all when it comes to hidden meanings.

The Human Condition is surrealism on another level. The painting is set inside a comfortable home, with a large window looking over natural tranquillity. At first glance, it looks as if we are staring out of a window, but a painting is actually obscuring the outside nature, the artwork’s clip and stand visible. In this work, the motif ‘reality is a matter of vision’ is bolded in red. It possibly refers to a recurring idea in Shakespeare’s plays. Fake belief, a unique human quality from the Cognitive Revolution: we must snap out of our dreams and enter reality. The Little Prince got it right after all. “What is essential is invisible to the eye.”

La Bonne Fortune (A Stroke of Luck), is another classic Magritte, depicting a cemetery for soldiers. Nonetheless, our eye is drawn to the centre, where an ‘elegantly dressed’ pig lies, a tie to George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The pose of the pig with his earring-like ears struck me, however, since there was something oddly familiar about it. The pig’s posture is likely a nod to the Girl With a Pearl Earring painting, where the portrayed figure looks behind: unnatural. This is more than likely, since Magritte superimposed Renaissance paintings post-war to make ends meet.

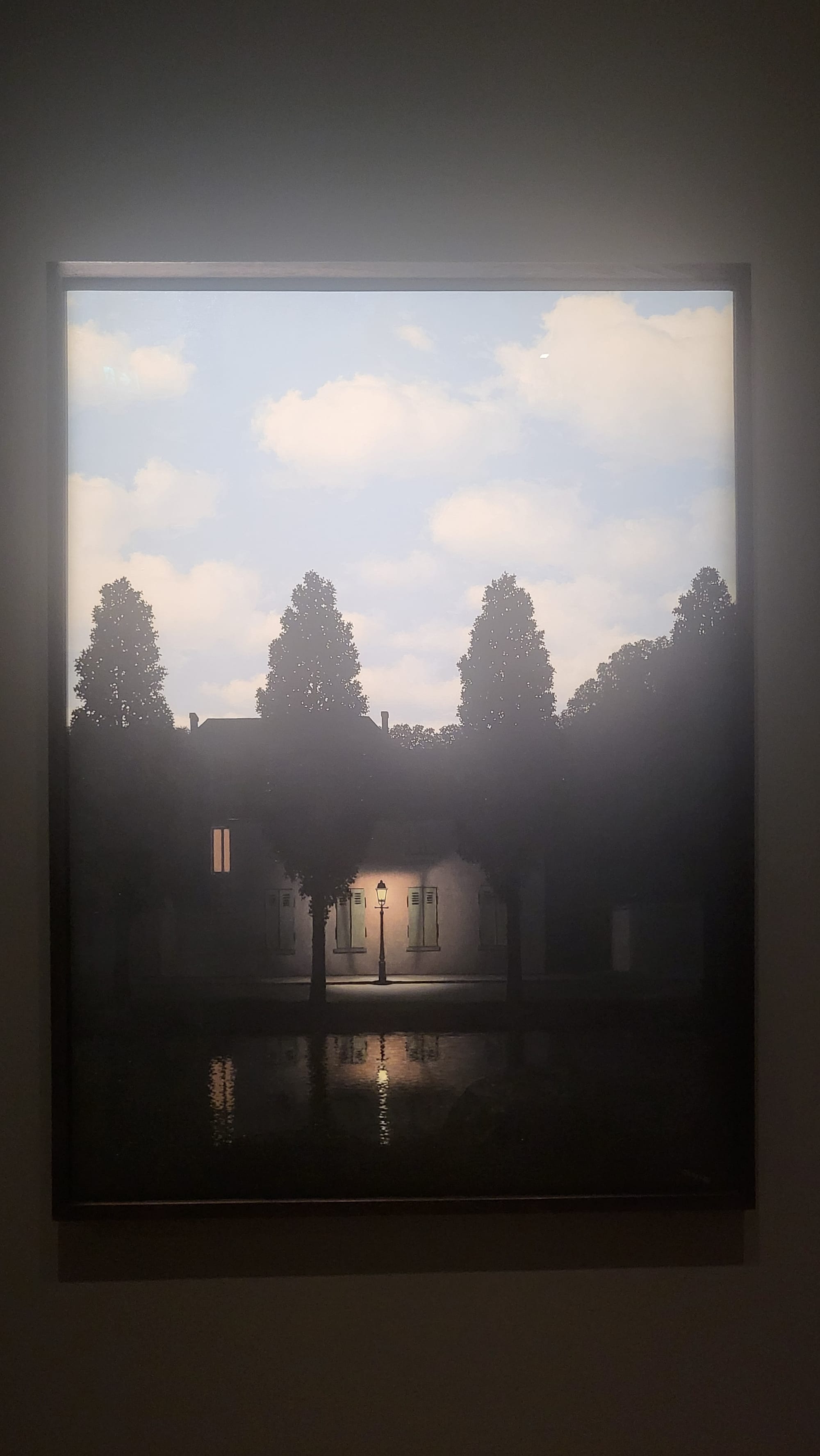

One of Magritte’s most juxtaposed artworks comes from a series of 27 paintings (17 oil, 10 guaches) called the Empire of Lights, which recently sold for a record-breaking 121 million USD. Originally meant for Peggy Guggenheim, he made 23 more replicas due to demand. Solomon Guggenheim, influenced by Peggy, wanted to add a Magritte to his collection. This work directly contrasts between dark and light, the tinted blue sky dawning on a dark house below. The pictured streetlamp sheds light on flowing water below, while a small silhouette is situated, watching: a rock. The lamp offers a sense of protection and warmth, but light and dark conflict at the centre of the canvas, as day and night are mixed together in the work. This evoked in me one of Louise Bourgeois’ quotes I learnt from her exhibition: “Has the night invaded the day or has the day invaded the night?”

Rene Magritte painted with ease, yet explained that painting was a ‘boring’ hobby to him, instead reflecting on ‘problem’ pictures. In a Variation on Sadness, a hen looks upon an egg in an egg cup, while a freshly-laid egg sits on the other side, experiencing a sunrise or sunset. Life and death come alive in this painting, for the egg in the cup is devoid of any life, while the abandoned egg has a chance of survival: the emphasis of the distinction between importance and reality.

Magritte’s works have surpassed the surrealist’s dream, keeping people at his exhibitions for hours. His thought experiments such as The Lovers and juxtaposing paintings like the Empire of Light and Variation on Sadness render us constantly amazed. Magritte never fashioned himself as an artist, but a writer and philosopher, seeing art as a mystery. I’m currently in the process of planning for my next Magritte adventure, consulted by my friends with a haemorrhage of questions.

Member discussion