The Light Nam June Paik Left Behind

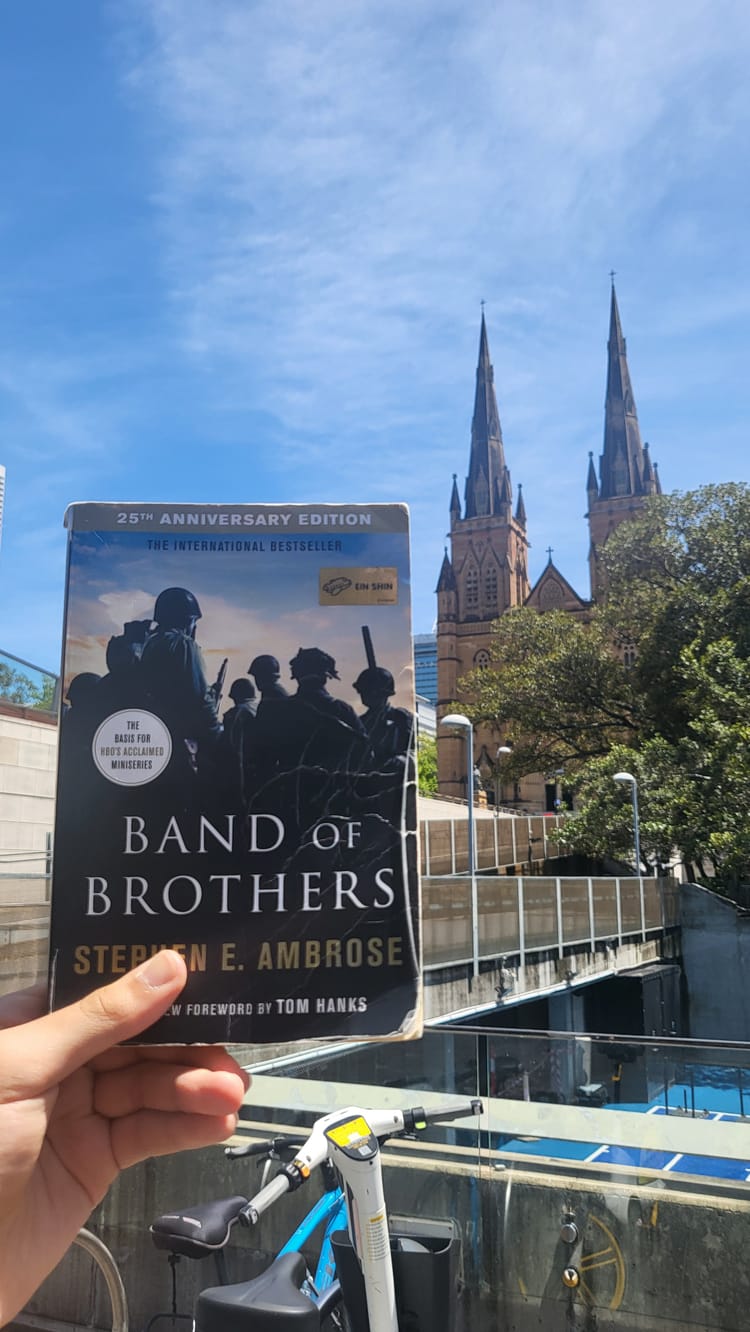

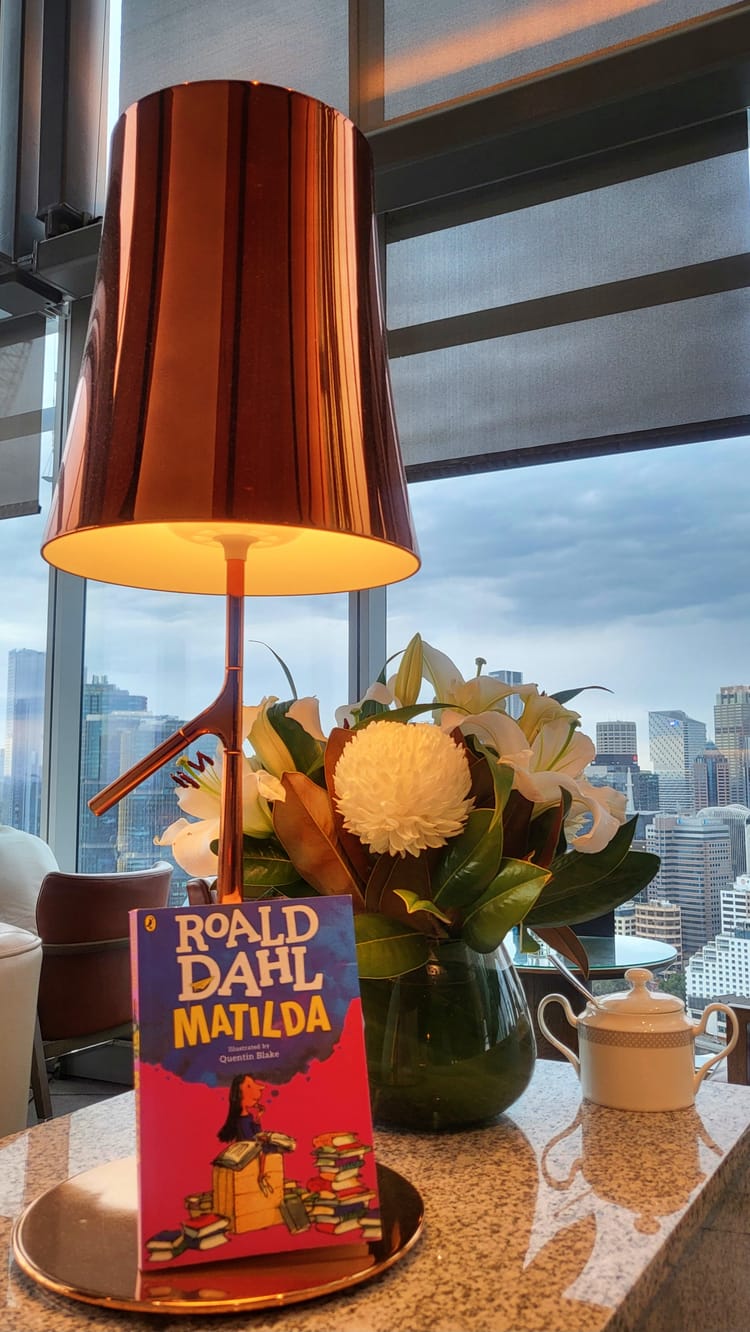

Figures 2, 3. (Left and middle) Enjoying drinks and reading books in the hotel lobby! Figures 4. (Right) Lot 666 hangs above our heads in the Gangnam Imperial Palace hotel.

During my absence from my blog, I was on a family trip in Korea, enjoying daily strolls and logging new memories while chugging Pocari Sweat. We stayed in two hotels, including the Grand Mercure Imperial Palace in Gangnam. I had never seen so many mirrors, lamps, and cushioned chairs in one place. A chandelier fit for The Phantom Of the Opera’s Lot 666 hung over our heads as we entered.

Figure 5. (Left) Us three children admiring More Logs in Less Logs Figure 6. (Right) More Logs in Less Logs awaited us.

In the lobby stood an artwork. It was an arrow made exclusively out of archaic TVs pointing upwards into the heavens while a video looped: More Logs in Less Logs. I was shocked that it was made by one of Korea’s and the world’s most influential artists: Nam June Paik.

I found that Paik stacked old wooden televisions to form a tower that somewhat resembled a digital pine tree, with video screens acting as glowing ‘logs’. We can share more stories and information through technology while cutting down fewer trees - achieving ‘more log’ with ‘less logging’.

Nam June Paik played with the inference that art will extend to more than just a simple canvas in the future. In essence, there is no future without technology. The shape of the arrow and its motion moving upwards suggested to me that moving on is inevitable, thus citing the importance of how we use technology to our advantage. His work somewhat encourages us to think about how we use modern tools and the impact they have on the environment.

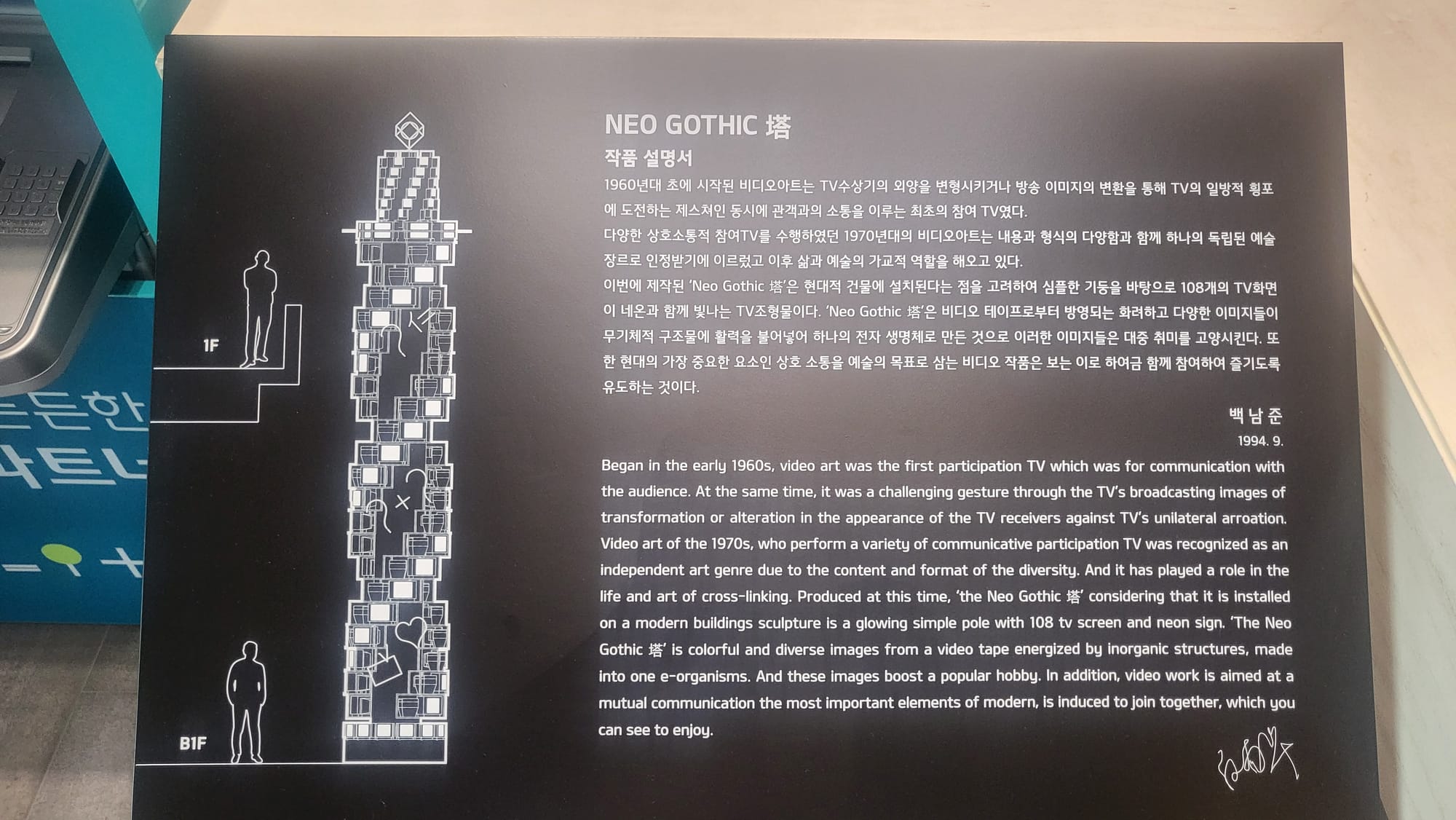

Figure 7. (Left) Neo Gothic Tower by Nam June Paik, Kia display hall exit Figure 8. (Middle) Display plaque Figure 9. (Right) Cheese!

The next morning, my father told us that he had found a Kia exhibition where we could ‘experience’ the latest car models. Our eyes twinkled as we ignored the sticky weather and walked the Gangnam streets. After carefully inspecting new electric vehicles, we three children left the oval setup of the display room with a drooling mouth, dreaming of exiting the exhibition with an electric car. So much we almost missed the top of a towering spiral of TVs popped up by the exit. There was something familiar about the artwork, the same unconventional art style immediately distinguishable. My jaw slackened as I read the bolded name on the plaque on the artwork: Nam June Paik.

I smiled. “Hello Mr Paik! We met at the hotel yesterday, and now you are here as well!”

Nam June Paik’s Neo Gothic Tower took the shape of a circular staircase moving to the top, namely, a neon cube. Only, this staircase’s steps were small TVs. Perhaps technology could become a new kind of spiritual and cultural space. The stack of 108 relatively old televisions morphs into the shape of a Gothic tower, yet instead of the usual stained glass and stone, he replaces them with moving images and electronic light.

The neon cube floating on the top of the work remained a sort of a mystery for me for a few seconds. It vaguely reminded me of a star atop a Christmas tree. However, now I find it rather as the crystallised frame of perception and the meditation on technology and interconnectedness. In this final form, the image becomes thought, and the structure begins to see. These mechanical ‘organs’ communicate across screens, forming a new kind of collective harmony, videos playing in unison. Through this, we imagine videos not just as entertainment, but as a space for reflection, connection, and shared experience in the digital age: inorganic, but organic.

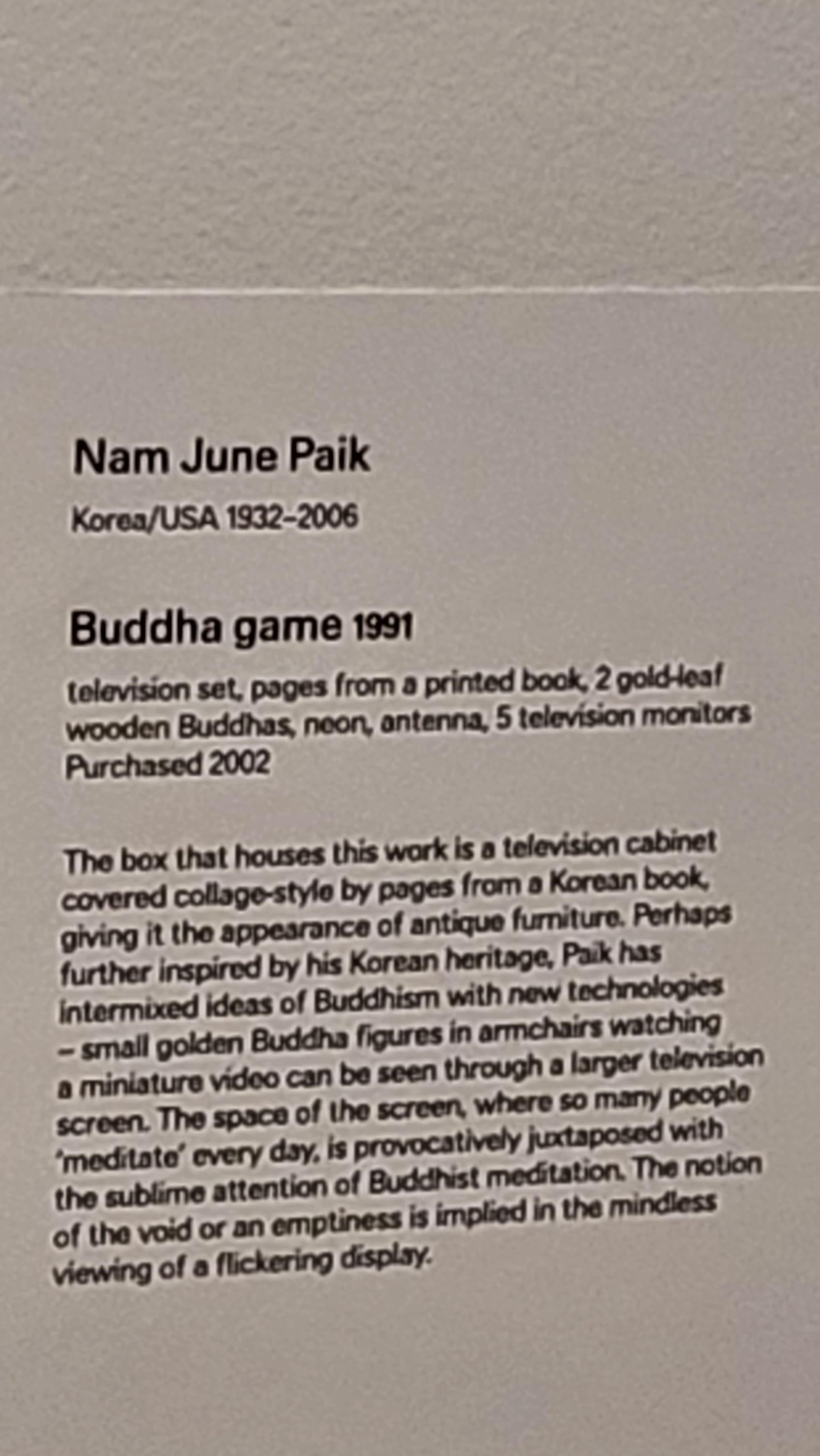

Figure 10. (Left) Buddha game by Nam June Paik, Art Gallery of NSW Figure 11. (Middle) Display plaque Figure 12. (Right) Inspecting Buddha game.

As soon as I arrived in Sydney, I realised that one of Nam June Paik’s works resided at the Art Gallery of NSW and went to ‘meet’ it. While Buddha Game is a smaller work in comparison to the two others I had seen, its own definition more than made up for it. Two Buddha figures sit facing televisions within the space where the screen of an antique TV would normally reside. As a minutia, pieces from a Janggi set scattered on the floor: a mix of old and new. The TV is covered with pages from a Chinese book, with Paik written on the right side of observation.

The piece instantly reminded me of Mr Harrigan from Mr Harrigan’s Phone. Mr Harrigan, who was a Luddite prior to his protégé, Craig, gifting Mr Harrigan an iPhone. From then on, Mr Harrigan manipulated technology to its advantage, similar to the motifs of Nam June Paik. The work is a loop of endless reflection, a quiet meditation on self-awareness, surveillance, and perception. Paik merges ancient stillness with modern technology, suggesting that enlightenment in the digital age may come not from escaping screens, but from learning to see clearly through them. Buddha Game becomes a digital shrine - not to worship, but to pause, to notice, to question. For me, it’s a meditation of how we view ourselves through technology and whether we are truly awake, or just asleep, staring into the TV.

Often, individuals fear technology. While they have reason to some extent, Paik seemed to believe the opposite. To him, technology wasn’t the end of a vicious cycle, but the reincarnation of contemplation, collection, and tenderness. His works don’t warn us to turn away from machines. Rather, they ask us to look more closely at what they show.

With Nam June Paik in mind, I naturally thought of Do Ho Suh, who I almost see as a successor, continuing to explore human presence through innovative technology. Do Ho Suh, too, used robotic-arm embroidery, immersive video art, and mechanical sculptures, his work suggesting that technology can be a vessel for thought, memory, and feeling.

Both artists remind us: technology isn’t to be feared, but understood and shaped with imagination. In human hands, innovation becomes creation.

As of now I am looking at my computer screen: my own window into insight!

Member discussion